Mike's Musical History

photo by Tom Corcoran

Mike was born and raised in Minneapolis. He sang in choirs all through high school and college, but the real spark that started him on his musical path was his discovery of the piano and improvisation. He stumbled upon his ability to improvise quite by accident toward the end of his senior year of high school. What followed was a rapid and passionate musical immersion, which lead quickly to his first Rock and Jazz Fusion band experiences.

Those initial piano exploration/improvisations happen with, (and really because of) Mike's friend Bear. The same thing was happening to him, and one day Mike just happened upon him monkeying around at the piano and joined in. Amazingly, there's actually a photograph of one of these initial piano encounters with Bear. (What are the odds? Remember, there were no cellphone cameras in those days.) The picture was taken in the Waconia High School choir room one day after school, and shows Mike and Bear immersed in joyous exploration. Not long after this, they would be in a band together.

It wasn't until years later that Mike realized that his improvisational musical abilities, were an innate talent. This lead naturally to composition. His head is always filled with music that he strives to filter into satisfying musical forms, and he didn't think this was anything special or unusual until he had met and worked with many other musicians.

This is a picture of Mike's first band, straight out of high school. Left to right, that's Mike, Dean Ward, Joel Rundell and Scott Makela. (Bear joined the band shortly after this photograph was taken.)

photo by Scott Makela

photo by Dave Sorensen

Mike's early self-taught musical roots would eventually lead to a formal musical education. He went on to receive a Bachelor of Music degree in music composition and theory from the University of Minnesota, where he studied with Dominic Argento, Eric Stokes, Lloyd Ultan and Paul Fetler.

After college, Mike started his own music production company called Intuitive, which evolved into a general audio and related media production company over time. It has provided him with a living since the mid 1980s, not to mention a facility in which to pursue his personal art music work.

The picture below shows Mike in the 1980s, seated at his keyboards with a couple of his pyramid demo tape mailers. Mike designed these packages to contain the first demo tape that he sent out to prospective commercial clients.

photo by Tom Corcoran

It wasn't long after Mike began doing music work for corporate clients, that he made what was for him an important distinction, or separation, between the music he created for clients and his own personal "art" music. This is not to say that he doesn't care about the quality of the work that he does for clients. It's just that he sees a distinction between the two. It is really one of craft vs art. The work he does for clients is his craft, and he brings as much of his artistic sensibilities to it as the project will allow. On the other hand, when he is creating a personal art music piece, he answers to nobody but himself. He is only trying to create music that he finds aesthetically and emotionally satisfying on a deeply personal level. The two sensibilities have a way of reenforcing each other. The composition and audio production work that he does for his clients is constantly developing and refining his skills, (his craft), which in tern improves the quality of his art music. While his art music work is constantly pushing him to go beyond his comfort level, break boundaries, learn new skills and techniques, and develop his ability to express with his music the inexpressible core of who he is as a person. This expressive ability then feeds back into his client work, making it richer and stronger. It's a somewhat symbiotic relationship that serves to enhance both.

An obvious advantage to this duel track approach to creating music, is the removal of commerce from Mike's art music making process. He is not reliant on grants and commissions to cover his expenses, though when those cash infusions come they are always welcome and helpful. Not having to subordinate his artistic vision to that of another, gives his music a more purely personal character.

Mike's compositional techniques and processes have gone through many changes and refinements over the years: from strictly prescribed through the use of conventional music notation, to guided improvisation, but improvisation in some form has always been at the heart of his music. Even the strictly noted music comes from improvisational source material. In fact, now more than ever, Mike sees his compositional process as a kind of slowed down improvisation. His work is constructed in a very linear through-composed fashion, with ideas growing, developing and transforming from one to another in an organic evolutionary way. He is always striving to tap into and trust his own innate musical instincts; giving them preeminence over self-conscious formalism. He's often been known to say things like "when making a compositional decision, do the thing that makes your music feel right to you, regardless of whether or not it's the thing the makes sense".

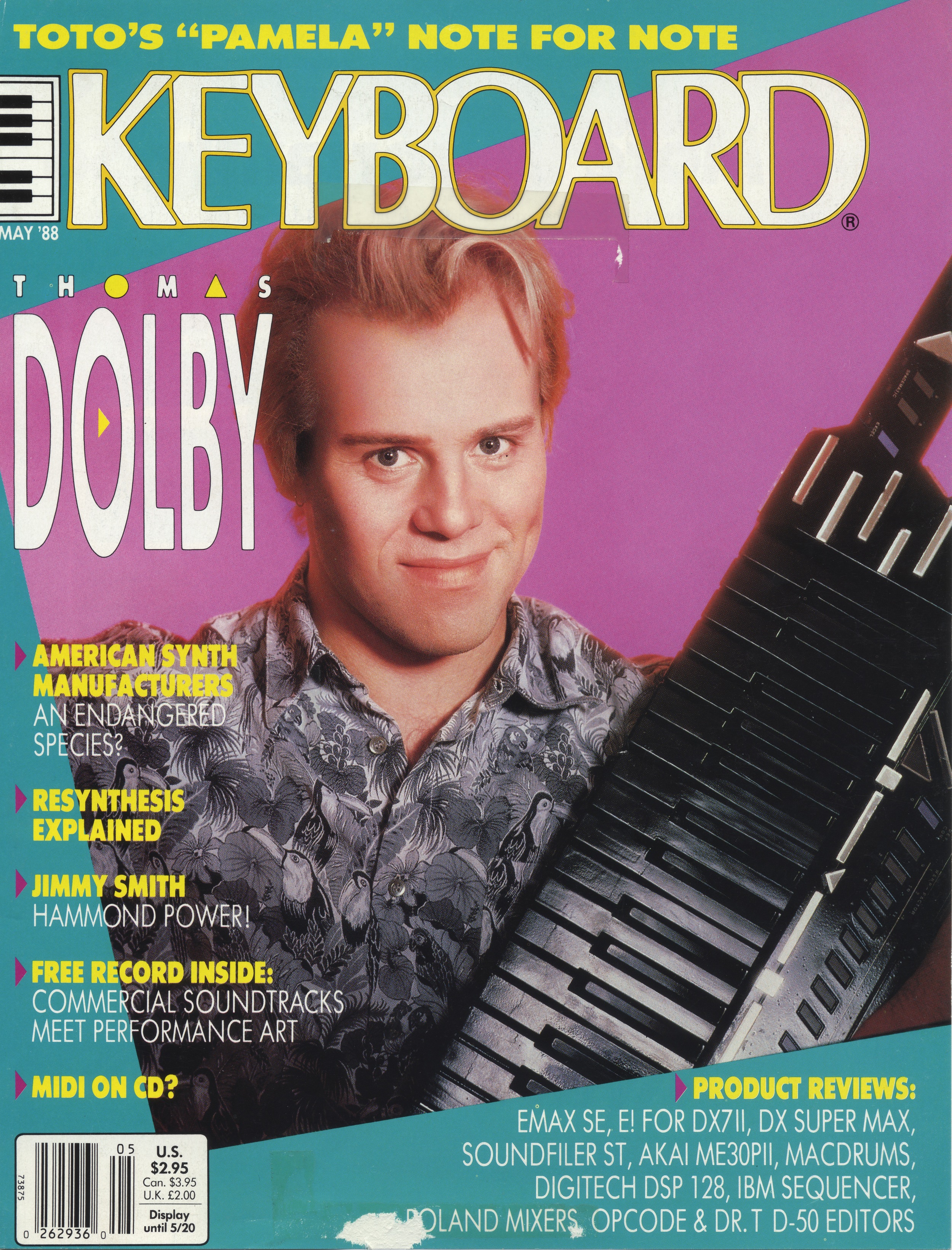

Mike was always a fan of Keyboard magazine, particularly in the earlier years when he identified much more as a keyboard player than a composer. So, he took some pride in being selected as a "Discovery" in May 1988 issue of Keyboard.

photo by Tom Corcoran

Keyboard "Discovery": May 1988

"Style: Electronic. Age: 29. Influences: Frank Zappa, Jimi Hendrix, Miles Davis, cartoon music, The Residents, Ornette Coleman, John Cage, Brian Eno. Main Instruments: Macintosh 512K with Mark Of the Unicorn software,

Yamaha KX88, TX816, REV7, D1500 digital delay, CP-80, and three SPX90s, Akai S900, Minimoog with JL Cooper MIDI interface, LinnDrum. Contact: mike@totallyintuitive.com.

Mike Olson reports that the Twin Cities' music scene is burgeoning as never before. The town treats him well: He has received a McKnight Fellowship for composition, numerous commissions for compositions, and enough work for commercials and industrials to support himself.

Recently, the prestigious Children's Theatre commissioned him for a production of Mall Dolls. Another recent commission, Enigmatic Interludes In South Minneapolis, exists in two forms – the original for bassoon quartet and the second for Olson's keyboard setup.

Olson's work will be included on several forthcoming recordings. The first piece features prepared electronic piano; this will be one of five pieces on an Innova Recordings CD called Freefall. (For details, contact the American Composers Forum: jmichel@composersforum .org) The second, a soundtrack for Scholastic Books, features electronic music for children's stories, which, Olson gleefully states, "I made as zany as I could." In addition, publishers Fedogan & Bremer (fedogan@millenicom.com) have just released a cassette of readings of 36 H. P. Lovecraft horror sonnets with Olson's scores."

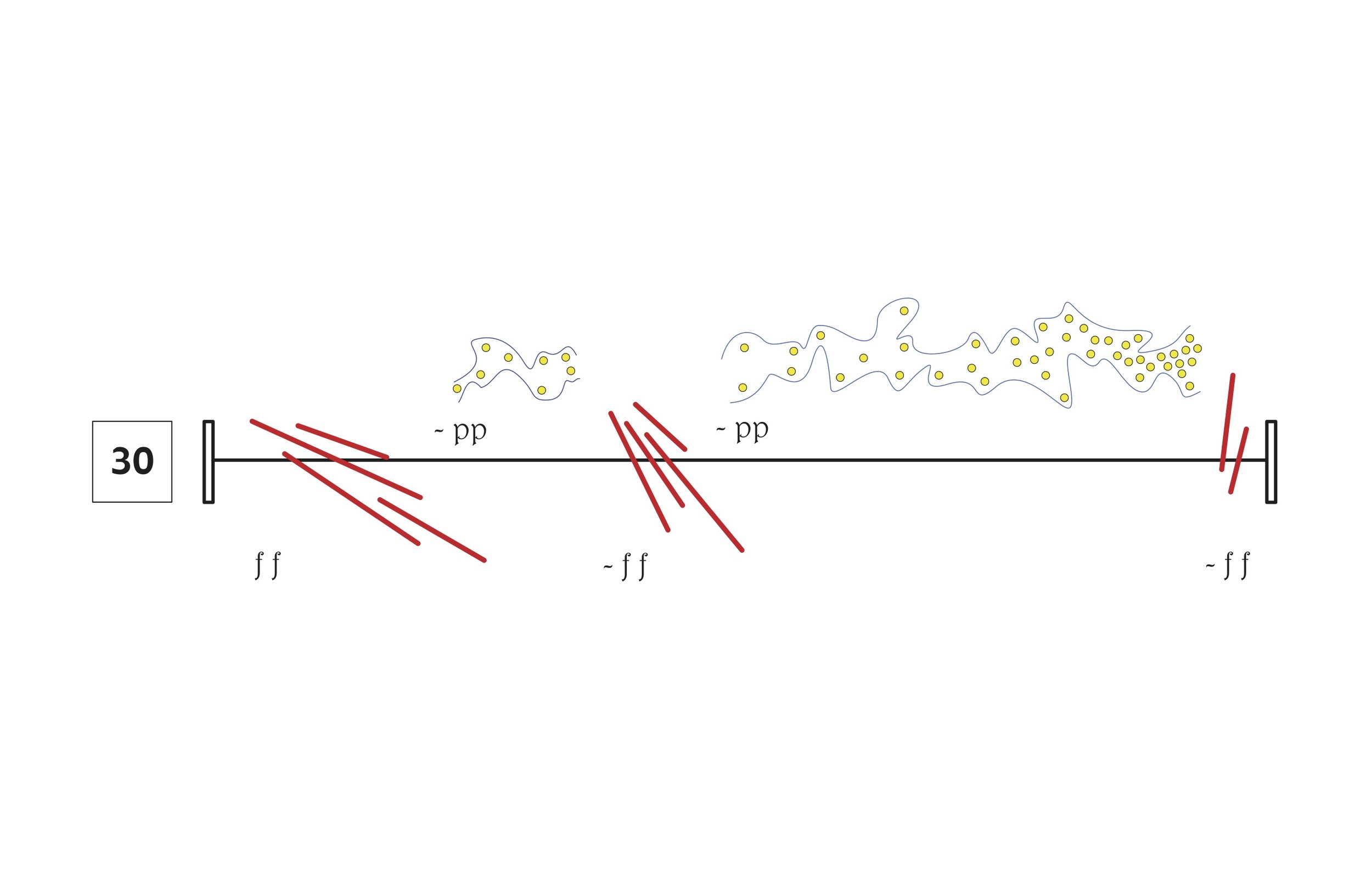

In 1990, Mike's piece "The Basketball Scenarios" was presented at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. Though the piece was well received and resulted in Mike being offered a full evening length concert of his own works there at the Walker, Mike was ultimately dissatisfied with the piece. He felt it worked as a piece of performance art, with the visual theatrical aspects of the piece functioning well to provide a satisfying multi-media experience, but for him the bottom line was - he just wasn't happy enough with how it sounded. This resulted in Mike taking a step back and seriously reassessing his work.

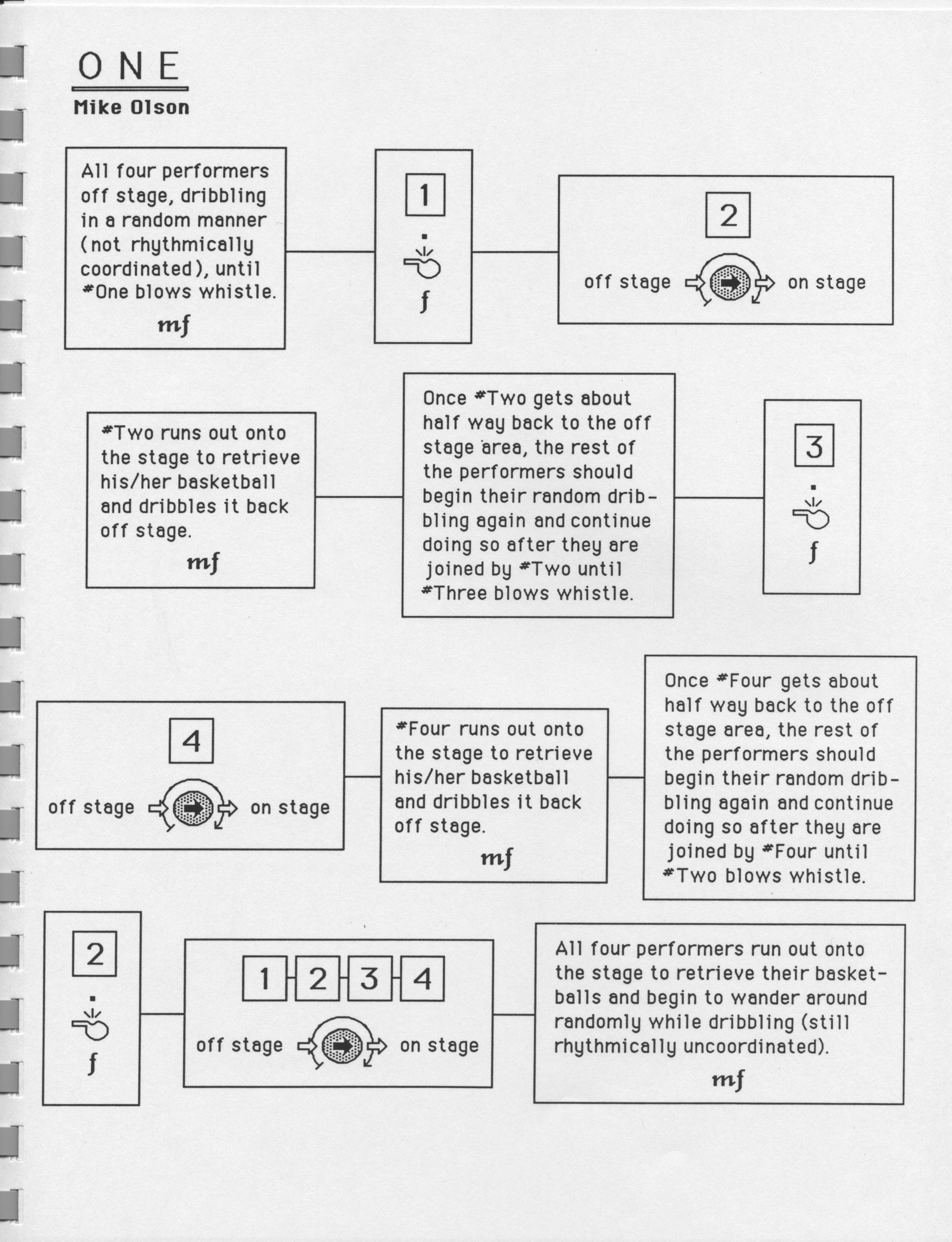

His next piece, "Song of the Badger", marked what would be for him a new beginning. He abandoned the idea of beginning work on a composition with any sort of a plan or conceptual framework, and instead just set out to write a piece of music that sounded and felt right to him from moment to moment all the way through. The piece was written for the contemporary music ensemble, Zeitgeist. So, his guiding limitation would be that it would have to be a piece of music that could be performed live by that ensemble. The entire piece was strictly notated, with some aleatoric interpretive graphic notation elements thrown in. He began by composing an opening gesture. Once he was satisfied with how that sounded, (and felt), he listened through it carefully repeatedly and tried to feel what should come next. He wrote that bit of music and then listened through from the beginning again, including the new material and tried to feel what should come after that. This is the slowed down improvisation idea mentioned above. The process of listening through and feeling what should come next was followed through the entire construction of the composition, resulting in a highly linear through-composed piece of music that was unlike anything he had done before. This ethos of trusting his musical instincts and avoiding self-conscious formalism has remained central to his approach to music composition since that time and he continues to refine it to this day.

Score page from "Song of the Badger"

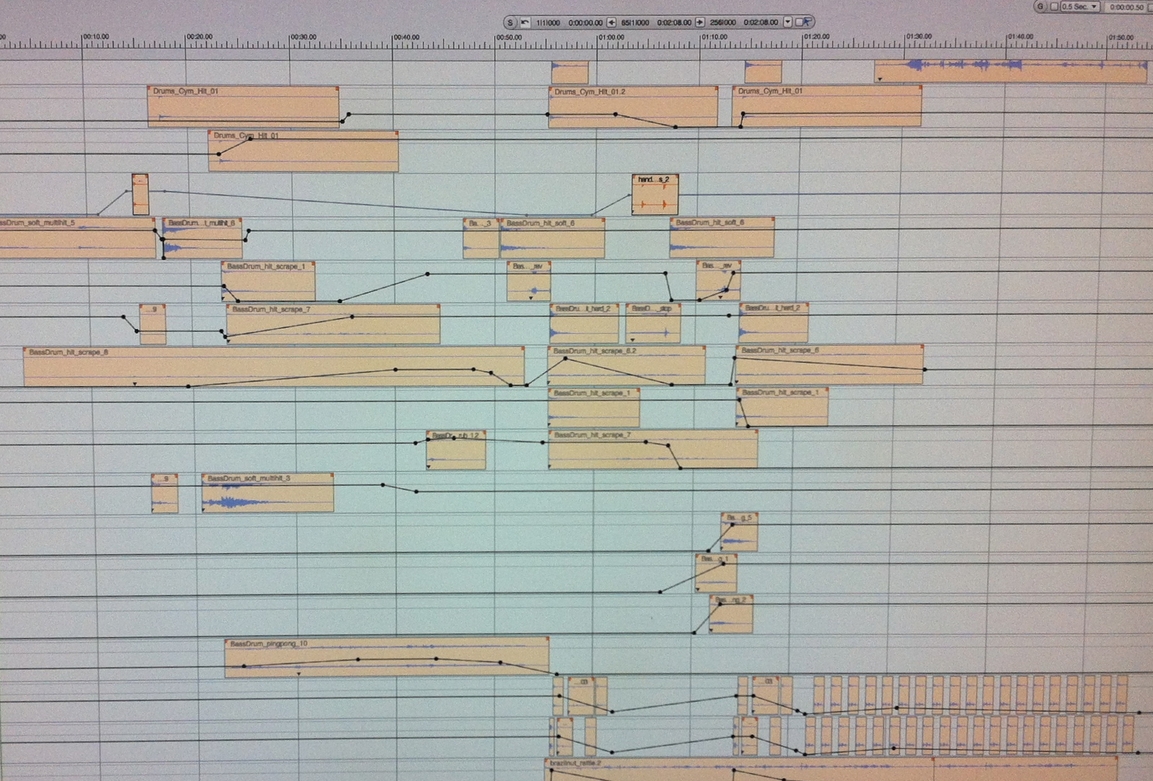

The next big change in Mike's compositional life would come in 1992. He had just finished his piece, "Antiphonal Winds", a conventionally notated work for double woodwind quintet and piano. He would now make a radical departure from this type of composing. The transitional piece was a studio project entitled "Shift". In it, he essentially constructed a Minimoog performance in the last section of the piece by means of digital audio editing. That was the first step into a new world of music making. What followed was a headlong plunge into a completely new way of creating music. In his next piece, "Actual W", the worlds of digital audio editing and music composition became fully merged into a new fragment-based compositional process. The piece is created entirely from musical fragments taken from other preexisting recordings. He was at first concerned that he might be misappropriating the work of others, but he soon discovered that he could create truly original new work using this technique.

Screen shot of fragment-based composing for the piece "De Novo".

This movement into his new fragment-based method of composing has been revolutionary and transformative. Mike has retained his highly linear through-composition ethos and taken it to a deeper level through the implementation of this technique. It combines the three elements of audio recording and editing, musical performance, and the manipulation of musical materials into one tightly integrated process. This was a natural evolution for him. In the years leading up to this change, he had spent thousands of hours doing computer-based digital audio editing. As the power of these editing tools and his own technical skills using them developed over the years, he began exercising a finer and finer level of control over the recorded material. Eventually, he found that he could create convincing new musical performances through the use of his editing techniques. He was able to take a number of discrete audio recordings of musical material, and then combine, edit, mix and process them in such a way as to create a completely new piece of music that sounded is if it was being performed by the musicians. Mike was now creating not only a new piece of music, but a new performance of that music. He was surprised to discover the degree to which he could manipulate, not only the musical materials, but the actual musical performance - the feel of the musicality of the performance.

This was a revelation for Mike. In the past, he would of considered it to be out and out heresy for anyone to assert that it was possible to create a musical performance that felt truly musical through means of computer-based audio editing. But the truth of his experience was unavoidable. He was constructing performances in the computer that sounded and felt as though they had been played by an ensemble performing together.

It should be noted that at the time Mike was developing this fragment-based method, he was on his own. He was unaware of anyone else doing anything like it. It was a natural outgrowth of his own life and experience with music and technology. He was exploring what was for him truly new compositional territory and there were no footsteps in the snow to follow. Of course now in retrospect, it is clear that many other composers have since come through similar transformations, and indeed, young people today are creating music using these computer techniques very naturally, seeing as working with recorded media on computers is just part of their DNA.

Mike's first fully realized fragment-based piece, "Actual W", was created from preexisting recording of music, some sound effects and some George W. Bush speech fragments. He then went on to create three more pieces constructed entirely from preexisting material. The first of these was "Short Black Winter". It was created entirely from musical fragments extracted from three Kronos String quartet recordings. This piece showed noticeably more refinement and control. Then came the piece, "What They're Doing", which was constructed from fragments extracted from live recordings of the contemporary music ensemble, Zeitgeist. By now, Mike was becoming well acquainted with what constitutes a useful musical fragment. "Dick and Don" was the last of the fragment pieces to use preexisting material. It was constructed entirely from Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld speech fragments.

This is a graphic score fragment from the piece, "Incidental".

After "Dick and Don", Mike was ready to start creating his own musical fragments from scratch. He set to work on a major new six-movement fragment-based composition entitled "Incidental" in 2004. It would employ 18 musicians and would take a number of years to complete. The project used a small amount of conventional music notation, but the vast majority of Mike's communication with the musicians was done through verbal instructions and graphic notation. He was careful to select musicians who had strong improvisational abilities, but were not bound by traditional Jazz improvisa-tion conventions. The resulting music constituted for Mike what he would consider to be the strongest and purest musical expressions he had yet been able to achieve through composition. He considers this the beginning of his mature period as a composer.

This is a verbal instruction from the score for the fragment-based choral piece, Noopiming.

Sing a series of random notes of your choosing on the vowel sound "u" (long). Fade in and out on each one and keep them relatively short. Randomize both the duration of the notes that you sing and the amount of silence you leave between notes – do not imply a rhythm. Avoid rhythmic entrainment with other singers around you. As a group, you should all be singing different notes of different durations with different amounts of silence between notes. Make each note beautiful. Keep the group sound going until you are directed to stop.

2013 marked the next significant change in Mike's compositional work. He describes it as being a kind of awakening. He'd been involved with electronic music to one degree or another since the 1970s. His path followed the development of the technology, starting with analogue synthesizers, then digital synthesizers and samplers, MIDI sequencing and on into the seemingly inexorable logic of the all-in-one-box computer-based electronic music vortex.

Then one day he stumbled upon something online that drew him to a shop in his neighborhood. He walked through the door and received his first introduction to eurorack analogue modular synthesis. This is something that he had been completely unaware of. He'd heard of small companies trying to make a stab at reintroducing analogue modular’s by offering do-it-yourself kits or flakey approximations of the Moogs of yore, but he had no idea that in recent years, there has been an explosive, if somewhat underground, renaissance in the development of hardware-based analogue modular synthesizers.

This was an earth shattering realization for Mike. What followed were weeks of online research. There are currently approximately 100 companies building analogue synthesizer modules. These are small companies – usually just a few people. They're creating these modules because they're passionate about what they're doing. It is unlikely that anyone is making a lot of money at it. The market is relatively small. That's why none of the major electronic instrument manufacturers have gotten into it. What's happening right now, is what I'm sure will be a very temporary and intensive flowering of creative output by these small companies. Most of them probably won't be around in a couple years, if for no other reason, because the electronic components used to create these analogue modules are going out of production and are disappearing world wide.

Closeup of some of Mike's eurorack analogue synthesizer modules.

photo by Mike Olson

Mike is now exploring this exciting new world as though he were exploring a garden filled with fantastical flowers of every description – some familiar – some bizarre and alien – each unique and beautiful in it's own way. This process of discovery has reawakened something in him that is difficult to put into words. It has changed the course of his work. To say that it has been stimulating would be an understatement. To quote Mike directly, "Quite frankly, I didn't know that I was still capable of being this strongly stimulated by anything when it comes to my art, at least in terms of technology and process."

It's kind of like going back in time and forward in time, at the same time. Forward, because of the explosively creative hardware developments mentioned above. Back, because these developments are being spurred by a longing for something from the past that has been lost. Of course, analogue modular synthesizers have their roots in the 1960s when Moog and Buchla developed the first commercially available instruments. These were handmade assemblages of various sound generating components, referred to as "modules", that were interconnected to create sounds using patch cords plugged into jacks on their front faceplates. These instruments were prohibitively expensive and primarily the province of Rock stars, major recording studios and educational institutions. Over time, synthesizer technology underwent numerous major advancements, but with each "advance", something was lost. These were usually considered insignificant losses compared to the new capabilities afforded by the latest advancement, but eventually, synthesizer technology had advanced so far beyond it's origins, that those seemingly small losses amounted to something truly substantial.

Those of us who had hung on to one or two of our old analogue synthesizers, began to develop an increasingly strong appreciation for their somewhat idiosyncratic sonic characteristics. It's a case of what is sometimes referred to as "lost technology". Quality vintage Moog instruments are now highly prized and sought after by electronic music aficionados around the world. Mike is the proud owner of two such instruments, which, much to his amazement, he is now rediscovering anew as he directly inter- patches them with his new analogue modules. A combination of the old and the contemporary, quite literally working together synergistically as one to create something new.

Another aspect of working with this technology that Mike finds strangely compelling is it's inherent ephemeral nature. It's not like working on a computer. You can't really save anything. You might spend hours or days developing a patch, and if you want to capture that sound, you have to record it. There are those who spend weeks or even months developing complex patches. They then listen to it for a while without recording it, before completely unpatching it. Very much like creating a sand painting. It seems a little crazily counterintuitive to find this kind of thing attractive in this age of computer-based work with multiple backups of everything and complete documentation of all aspects of our work on the cloud, but Mike kind of likes it. He knows he'll never get the same thing twice. Even if he were to completely recreate the patch exactly the same, it would be different, because the slightest differences in voltages resulting from small variations in resistance due to contacts in the jacks or the slightest of differences in knob settings, will result in the patch behaving/sounding differently. So, when he get something he really likes, he does record it.

Mike continues to create highly linear through-composed fragment-based compositions using analogue modular synthesizers to this day and is having the time of his life.

Ten Important Events in my Development as a Composer:

When I applied for a McKnight Fellowship in 2018, the application asked for this list of ten events. They offered this as an option I could choose instead of sending a resume. I thought that was an interesting idea, so I wrote up the following list. It took a fair number of hours, and it was only once I had completed this 8-page document that I noticed the guidelines called for this to be a 2-page document. My heart sank. So, I decided I'd post it here.

1.) My exposure to music which was created to reinforce visual activity.

In particular, television and film. Like many people of my generation, I grew up in front of a television. Consequently, I was exposed to a great deal of music that was written to work with and reinforce action or emotion on the screen. It wouldn’t be until much later in life that I would become aware of how much this exposure would come to shape my musical sensibilities. Over the years, my compositional development has gone through many stages and I have written in many styles, but the music I’m writing today as a mature composer still sounds visual to me.

2.) Discovering improvisation at the piano.

Toward the end of my senior year in high school, I stumbled into improvisation with a friend. We just sat together at the piano and explored. Neither of us had any experience at the keyboard. This was a profoundly formative experience for me. What I didn’t realize at that point in time, (and wouldn’t for quite a few years to come) was that I had innate musical talent. Improvisation came completely naturally to me. New musical ideas were always present in my mind and available for me to access. I was soon pouring myself into the piano every day. The creative musical spigot was open.

3.) Becoming a self-taught musician playing in and writing music for Rock and Jazz Fusion bands.

Within a year after my discovery of the piano, I was in my first band. Over the next five years or so I worked in a number of bands, and all but one of them played originals exclusively. This gave me the opportunity to compose a lot of music right away. Almost all of the musicians I worked with played entirely by ear. There was almost never anything written out. Everything was memorized.

4.) Receiving a Bachelor of Music degree in music composition and theory form the University of Minnesota.

Being self-taught, I didn’t have the usual academic background of students entering an institution of higher learning in music. For me, the barrier would be the audition. Even though I was going into composition, I would still be expected to have proficiency on instrument – in my case, the piano. I could play, but I had no Classical experience and could not sight read. I was however able to understand written music, having been in choirs all through high school. So I found out what I would have to play to pass my entrance audition, bought the sheet music and learned it. This got me in.

I loved my time at the University. Golden years of hard work and rich rewards. I completely immersed myself in my Classical music studies. My composition teachers included Dominic Argento and Eric Stokes. Two radically different composers who taught me many valuable lessons. That being said, it was during this time that I made the decision to not pursue an academic career, which was an unusual choice. Most of the serious composition students were already on track for a life in teaching at the University level. As much as I loved my University experience, I knew I didn’t want to teach, even though as my composition teachers would tell me, “that’s the way in works in America”. Secure a teaching gig and the school will give you time and encourage you to compose.

Choosing to not go the academic route was a major decision. I chose instead to pursue a career in commercial music and audio production as a way of supporting my art music career. I wanted to completely remove commerce from the equation when it came to my personal art music, and that’s what I’ve done. I create only the music that I want to create. I answer to no one but myself, (and I might add, I can be a stern taskmaster).

5.) Creating formal process-driven music, which eventually lead to a more conceptual approach.

Form and process are what drove my compositional practice by the time I finished-up at the University. It was captivating and I wrote a lot of music that reflected this. Over time, form gradually gave way somewhat to process and ultimately to a more refined conceptual approach to composition. I loved my conceptual pieces as ideas. They were fun to talk about and really kind of fascinating, but ultimately I came to feel that this was not what I wanted to do. I loved the purity of the conceptual process, but at the end of the day, the music was only satisfying on an intellectual level. There was no emotional connection for me.

This came to a head when I had one of my pieces performed at the Walker Art Center. It was a quartet scored for basketballs and referee whistles. (A nice limitation. Establishing meaningful limits is still a central tenant in my work.) It was a multi-movement piece with a lot of interesting and visual/theatrical aspects. The performance went well and the audience loved it. As a result, the Walker offered me a full evening of my works to be presented there. Something I never followed-up on and obviously should have, but my music was about to undergo a big change. Later, when I listened to a recording of the performance, I realized it was emotionally dead. I felt nothing from it. It was still interesting conceptually, but that’s all it was – “interesting”.

6.) Returning to my ear and the abandonment of formal constraints.

What followed was a watershed moment in my compositional life. The next piece I wrote was, “Song of the Badger” for the contemporary concert music ensemble, Zeitgeist. I threw all of my conceptual ideas out the window. My only constraints for the piece were, it had to be something that the ensemble could perform live and I had to love every moment of the finished composition. I would write the piece in a through-composed manner and completely by ear. I started out by writing the first measure, and when I was happy with how that sounded, I would listen through and try to feel what should come right after that. (I should note that I was developing the piece on MIDI instruments in parallel to the written score, so that I could hear an approximation of what it would sound like live.) I continued to use this rule of feeling and then writing what should come next all the way through the piece. It was like a kind of slowed-down improvisation. I did end up using some more conventional formalisms here and there, but they were in each case “the thing that would sound good next”. The end result was something that I really liked and it revealed to me for the first time my childhood television musical influences. (See item #1 above.) It sounded like cartoon music in places. It sounded like visual activity. This spurred me to seek out and listen to the music of composers like Carl Stalling and Raymond Scott. I embraced this new (old) ethos of writing by ear and more importantly by feel. This has since evolved to some extent, but it is still present in my music today. Another thing that this process does is it leverages my improvisational impulses, which are a manifestation of my innate musical talent. That is a good thing.

7.) The fragment-based composition breakthrough.

In the early 2,000s, I started noticing what some virtuoso turntablists were able to create by blending material from multiple turntables to make something new. This got me thinking about what could be done along these lines (and far beyond) in the computer. I had become by this time a highly skill audio editor. Digital audio editing was by this point completely second nature to me because of the work I had been doing for clients. So I could envision how various disparate sources could be used to create something new, but still, I was reluctant. I was very uncomfortable about using other people’s music without permission to create a new piece. But the idea kept nagging at me, and in 2002 I made my first fragment-based piece, “Actual W”. It uses preexisting music from various sources and some other non-musical sounds. I was very pleased with the result. Kind of shocked, really.

I then went on to create three more pieces using preexisting material. These were “Short Black Winter”, a piece using fragments harvested from three Kronos String Quartet CDs, “What They’re Doing”, a piece using fragments from a variety of pieces recorded by Zeitgeist, and “Dick and Don”, a piece using fragments harvested from a number speeches by Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld. With each of these three pieces, my technique improved as did my understanding of what made a fragment musically useful. I also became more confident that what I was creating was something truly new, and not some crude collage of easily recognizable chunks of other people’s music.

Two interesting anecdotes associated with the Kronos piece help to illustrate and reinforce this:

1. I used a lot of John Zorn fragments in the piece, because his compositional style generated a lot of very useable short and isolated gestures. So when the piece was completed, I sent him a copy of it along with a letter describing what I had done and asking if he had any issues with it. He called me up and told me that he loved the piece and that he didn’t notice any of his material in it. So, I was aware of every tree in the forest, but he just saw the forest, even though he was intimately familiar with some of the trees.

2. Shortly after having completed the piece, I happened to meet Joan Jeanrenaud, the cellist who performed on the three Kronos CDs that I had extracted material from. I told her about the project and sent her a copy of it. When she got back to me with her thoughts, she was under the impression that the whole opening section was one intact sample that I had lifted. This was both shocking and affirming, seeing as that section (like the rest of the piece) had been highly constructed from many fragments taken from a variety of different pieces. She did not hear it as a constructed piece, but rather as a played piece, and SHE was one of the original performers.

Another interesting thing about the “Short Black Winter” piece: After I had harvested all of my fragments from the CDs, I went through all of the fragments and painstakingly logged all of the pitch content from each one, so that I could refer to that information when constructing the finished piece. It took days. Then when I did the final construction of the piece in the computer, I never once referred to this document. I just used my ears, and it turned out great. I didn’t think that I would be able to do that.

8.) Creating original material to use in my fragment-based compositions and continuing to refine the process.

Now that I had done a number of these fragment-based pieces, I had a good sense of what made a fragment musically useful. So I set out to create my first fragment piece where I was creating all of the fragments from scratch. The project was, “Incidental”. A large 6-movement piece for 18 musicians. I used a small amount of conventional music notation, but mostly I relied on graphic notation and verbal instructions. The musicians were recorded individually or in small groups of 2 or 3. I ended up with a very large number of fragments. Too many really, (thousands) and I am very proud of the finished piece.

Note the name: “Incidental”. An acknowledgement of the visual character of my music. By this point I had fully embraced that this was just part of who I was as a composer. It is an integral aspect of my aesthetic.

This fragment technique combines recording, performance and the manipulation of musical materials into one integrated process. I’ve since gone on to create numerous compositions using my fragment-based composition process, which I am continually refining and improving. There is so much that I wish I could convey to you about this work. It’s difficult. That is to say, the really important stuff is difficult to convey. It always is, but I will try.

What makes music “good”? There are the musical materials – that which is quantifiable. Pitches, rhythms, dynamics, articulations, conceptual underpinnings, etc. And then there is the realization of those materials into sound. In other words the performance. I believe that though the musical materials are important and will always be of vital significance to the composer, they are something which must be transcended by the performers in order to achieve a truly musical result. For example: I’d rather hear a musically transcendent performance of mediocre material than a stilted performance of great material. Great material on the page is just a collection of ideas. It is only when it is brought to life in a linear unfolding sonic experience that it becomes music. And it doesn’t become “good” music until and unless the performance goes beyond what is on the page to a transcendent state of personal expression by the performer. For me, this is an axiomatic concept and is at the heart of my work.

Now comes the difficult bit. How is it possible for this to be achieved in my fragment-based compositional process? There can be transcendent musicality in the performance of the fragments that I record. I certainly strive for that, but the performance of the fragments is not the ultimate performance. The real performance is constructed in the computer as I assemble and mix the various fragments to create the finished work. Now remember, I construct the music in a highly through-composed manner, where I am striving to make it feel right to me from moment to moment. (Here comes the heretical part.) I have found that I can make the performance feel right through editing.

It is often the subtlest of shifts in timing or balance that unlock the beauty of the moment. As I’m working on this music in the computer, it has to not only sound perfect, it has to feel right from the very first note. I do this by completely immersing myself in the music as I play it back. I have to get my conscious mind out of the way and connect with the material on an emotional level as it plays. If at any point the feeling is broken, I know there is a problem with that particular spot. I hone in on it and make what I think are the necessary adjustments. It’s often very small time shifts of one of constituent elements using the arrow keys on the keyboard. Just one or two clicks. Then I have to back it up and play through it again with that same emotional investment and vulnerability and see if I can make it through the problem spot without the feeling being broken.

I know it sound flaky but I’m telling you it really can work. It’s also emotionally exhausting, but it works. And there is no way in God’s green earth that you could have ever convinced me that this is possible, before I had developed the method and experienced it myself. I would have said no, it has to be in the live performance of the material. But with this fragment method, I really am creating the performance and can achieve a transcendently musical result. I guess the proof is in the pudding. In each case, the end result is a perfect recording that feels right to me from start to finish. Maybe this is purely personal and nobody else can feel it, but I don’t really believe that. At any rate it is a pure and highly personal musical expression. So much so that the boundary between me and music starts to blur in my mind and experience. In my opinion, this is what all true art should be.

9.) The discovery/rediscovery of hardware-based modular synthesis.

I have discovered and fully embraced the old/new world of hardware-based electronic music via modular synthesis. It's kind of like going back in time and forward in time, at the same time. Forward, because of some explosively creative hardware developments. Back, because these developments are being spurred by a longing for something that has been lost. Of course, analog modular synthesizers have their roots in the 1960s when Moog and Buchla developed the first commercially available instruments. These instruments were prohibitively expensive and primarily the province of Rock stars and major educational institutions. Over time, synthesizer technology underwent numerous major advancements, but with each "advance", something was lost. These were usually considered insignificant losses compared to the new capabilities afforded by the latest advancement, but eventually, synthesis technology had advanced so far beyond it's origins, that those seemingly small losses amounted to something truly substantial.

Those of us who had hung on to one or two of our old analog synthesizers, began to develop an increasingly strong appreciation for their somewhat idiosyncratic sonic characteristics. It's a case of what is sometimes referred to as "lost technology". Quality vintage Moog instruments are now highly prized and sought after by electronic music aficionados around the world. I am the proud owner of two such instruments, which, much to my amazement, I am now rediscovering anew as I directly inter-patch them with the new generation of modules that I have been gradually acquiring. A combination of the old and the contemporary, quite literally working together synergistically as one to create something new.

One way in which my work has taken an unexpected turn as I explore this new/old technology, has to do with a new interest is patterns. I've never been one for looping or even using repeat signs in my conventionally notated material. However, when I added a sequencer to my modular rig, something unexpected happened. I started doing music with short repeating patterns that evolve over time. This is kind of "old fashioned" sounding to me in a way, but it's also new for me, seeing as it's something I've avoided in the past. I'm now doing work that shows a strong minimalist influence, without being truly minimalist. I'm also finding that there is a deep ocean of possibilities to explore in the realm of hardware-based sequencing through the implementation of techniques on purpose-built modules designed to interface with these sequencers, including random voltage generators, which extend the prospects for variability into the infinite. (Did someone say, “chance operations”?)

Another aspect of working with this technology that I find strangely compelling is it's inherently ephemeral nature. It's not like working on a computer. You can't really save anything. You might spend hours or days developing a patch, and if you want to capture that sound, you have to record it. I've heard of people spending weeks or even months developing complex patches, and then listening to it for a while but not recording it, before completely unpatching it. Very much like creating a sand painting. It seems a little crazily counterintuitive to find this kind of thing attractive in this age of computer-based work with multiple backups of everything and complete documentation of all aspects of our work on the cloud, but I kind of like it. I know I'll never get the same thing twice. Even if I were to completely recreate the patch exactly the same, it would be different, because the slightest differences in voltages resulting from small variations in resistance due to contacts in the jacks or the slightest of differences in knob settings, will result in the patch behaving/sounding differently. So, when I get something I really like, I DO record it.

10.) A return to live performance, (of a sort).

One thing that has happened as I’ve been working on fragment pieces using the modular synthesizers has been somewhat unexpected. In order to create a sound on a modular synthesizer, you have to build the sound from scratch by connecting (patching) various modules together and adjusting the voltages. For the most part, I am listening to the sound as I work on the patch, and it can take a while. What I’ve found is that some of the most interesting and useful sonic things happen while I’m working on getting to the sound I’m after. So, I’ve started recording myself while I’m working on the patching and I’m allowing myself to “go” with a tangential idea if something interesting and unexpected immerges. This process has started to become like little performances in themselves. I still don’t see this as finished work and I still go through what I’ve recorded to harvest out musically useful fragments to use in the final piece, but it has pushed me in the direction of doing live performances with these instruments.

I have now done a number of live electronic music performances with this technology. No computers. Just the hardware instruments. It’s been fun and stimulating, but the finished pieces I create are still made using the fragment method. I take a recording of the live performance as well as recordings of any rehearsals, and go through them, harvesting out all of the material I like best to create the final piece. I do however, tend to use larger sections of audio in these pieces. I guess my process may be evolving somewhat.

I am planning to do more live performances with this technology in the future, even though it is kind of hard to take out on a live performance. That being said, I do think it’s more interesting for an audience than sitting there watching someone stare at their laptop. I'm looking forward to seeing where all of this goes.